Sense of Coherence Self-assessment (medical)

When you think of heart health, you probably think of nutrient-rich foods, regular exercise, and excellent fitness. You might be surprised to learn that things like personal relationships, job satisfaction, sunlight, beautiful paintings, pleasant music, and so on are also important factors, too. You might be surprised to learn, for example, that patients who have undergone a significant surgery recover more quickly when there is a potted plant in their hospital room, or if the patient’s friends and family come to visit them while in rehabilitation.

Five-hundred years ago, the most common practice of medicine was called humorism. No, this isn’t the act of making patients laugh in order to help them recover, which was the plot to the movie Patch Adams. The word “humor” referred to the four basic liquids in the human body: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. It was believed that these four humors existed in harmony and balance. If this balance was upset, then a patient would get sick. Therefore, when a patient presented with measles or mumps or fever, the doctor assumed that the humors had become unbalanced, and they would use leeches or puncture wounds to drain some of the blood out. General George Washington, the founding President of the United States, died from complications of bloodletting to treat a bacterial infection. Reports suggest that 40% of his blood was drained during the procedure.

Today we know that what Washington needed was Penicillin, which is a prescription antibiotic. But this wasn’t known back then. Penicillin and other common medical drugs were the product of modern medicine. The normal human life expectancy has increased rapidly due to the benefits of modern medicine—sterilization, surgical procedures, antibiotics, nutrition, and hygiene have all played important roles. Modern medicine had been so successful at extending the human lifespan that the leading cause of death—which for many hundreds of years was infectious diseases—fell to the bottom of common causes.

Of course, something had to take its place. Infectious diseases have been replaced by a new most likely cause of death—lifestyle related diseases, such as heart attacks.

There are many factors that increase the likelihood that your heart or my heart will stop working. The problem is that none of these factors can be linked to heart attacks in 100% of cases. Smoking cigarettes, for example, enormously increases the likelihood that you will have a heart attack. But by smoking cigarettes you are not guaranteed to keel over from a major cardiac event. American author Kurt Vonnegut playfully threatened to sue his cigarette manufacturer because, for over 40 years, the manufacturer, by way of little advertisements printed on the cigarette packs, had promised to kill him. But Vonnegut hadn’t died.

Other factors that increase the likelihood of heart attacks include diet, inactivity, stress, genetics, stress, and so on. The more factors that are present, the greater the likelihood of a heart attack.

In the 1970s, a medical sociologist by the name of Aaron Antonovsky decided to devote himself to understanding the factors that predict major cardiac episodes. To do so, he decided to examine those people who were at the greatest risk for heart attacks. These people, it turned out, were those who had already survived one heart attack. These people, statistics demonstrated, were 67% likely to have another heart attack. These hapless folks became Antonovsky’s sample. He would examine their food, their activity, how they spent their time, how they interacted with others, how they felt about their lives and medical history, and so on. He would be taking a lot of notes.

What he found not only surprised him. It also changed the course of medicine forever.

Antonovsky observed three factors that, when present in a cardiac disease patient, reliably predicted whether they would suffer another cardiac episode. Remember that these were patients who were 67% likely to have another heart attack. The odds were already stacked against them. But, if these three factors were present, then Antonovsky could say with certainty that they were at the low end of the risk spectrum. It was bananas.

The most shocking part of his observations was that the predictive factors did not concern diet or exercise, smoking or other harmful habits. Not even genetics. The predictive factors had everything to do with the patient’s perspective about themselves and their medical problems.

During his study, Antonovsky spent many hours with heart trauma patients. He noticed how some heart attack patients coped well. They rested when they were supposed to rest; they changed their diet the way they had been asked; and they accepted the length of rehabilitation. Others coped poorly. They got up and moved around before it was safe to do so; they quickly returned to their normal diet; and they felt targeted by fate.

Antonovsky found that patients who understood their condition, felt confident and capable of following through on a treatment plan, and saw meaning in their medical condition would be significantly less likely to suffer another heart attack than those patients who showed none of these perspectives and behaviors. Together, he called these three factors “sense of coherence.”

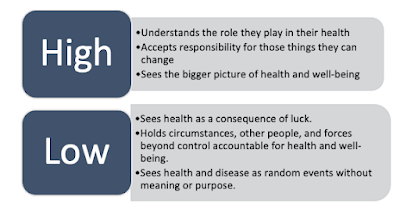

In Antonovsky’s observations, those patients who did not accept their medical condition and who did not accept or follow the treatment protocols—in short, those who had a low sense of coherence—believed that life events were random. They believed that they were not responsible for their medical conditions, and that they had little control over what happened to them. These patients with a low sense of coherence felt as though life happened to them. They did not see themselves as the central agent or origin of their lives.

We find the patient with a high sense of coherence in contrast. “At the other extreme,” Antonovsky writes of the high sense of coherence patient, “events in life are seen as experiences that can be coped with, challenges that can be met. At worst—and recall that these are people who have undergone very difficult experiences—the event or its consequences are bearable” (p. 17).

Figure 1.1: High Versus Low Sense of Coherence

Comprehensibility

Manageability

Meaningfulness

Sense of Coherence Inventory

“When you talk to people, do you have the feeling that they don't understand you?”

Writing Your Report

Once you have your SOC score, I want you to write an essay where you share your score and what it means. By itself, the score is just a number. In the report, I want you to explain what it means in the context of your life. What do you learn about yourself? What aspects of your life do you think contribute to a high sense of coherence? Which parts contribute to a low sense of coherence? And so on.

Structuring Your Report

I recommend the following sections:

1. An Introduction to Sense of Coherence. In a paragraph or so, explain in your own words what “sense of coherence” means, and describe the inventory.

2. The Results of Your SOC Inventory. Imagine that you are a health psychologist. Share your results from the inventory along with a few sentences about how you interpret those results.

3. Personal Reflection on What Your SOC Score Indicates. Write this section like a patient who has received their SOC results. How do you make sense of the score and analysis from Part 2? What does it mean to you? Does it seem accurate? Does the score miss part of the picture?

4. Plan for Personal Change. In this section, look forward. Is there something specific that you can do to increase your sense of coherence? What would that practice look like? What would need to change in your life?

A sample score and report can be found after the inventory.

SENSE OF COHERENCE INVENTORY

1. When you talk to people, do you have the feeling that they don’t understand you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

never have this feeling always have this feeling

2. In the past, when you had to do something which depended upon cooperation with others, did you the feeling that it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

surely wouldn’t get done surely would get done

3. Think of people with whom you come into contact daily, aside from the ones to whom you feel closest. How well do you know most of them?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

you feel that they are strangers you know them very well

4. Do you have the feeling that you don’t really care about what goes around you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very seldom or never very often

5. Has it happened in the past that you were surprised by the behavior of people whom you thought you knew well?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

never happened always happened

6. Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

never happened always happened

7. Life is:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

full of interest completely routine

8. Until now your life has had:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

no clear goals very clear goals

9. Do you have the feeling that you’re being treated unfairly?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

10. In the past ten years your life has been:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

full of changes completely consistent

11. Most of the things you do in the future will probably be:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

completely fascinating deadly boring

12. Do you have the feeling that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don’t know what to do?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

13. What best describes how you see life:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

I can always find a solution there is no solution

to painful things in life to painful things

14. When you think about your life, you very often:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

feel how good it is to be alive ask yourself why you exist

15. When you face a difficult problem, the choice of a solution is:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

always confusing and hard to find always clear

16. Doing the things you do everyday is:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

a source of deep pleasure a source of pain and boredom

17. Your life in the future will probably be:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

full of changes completely consistent and clear

18. When something unpleasant happened in the past your tendency was:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

to “eat yourself up” about it to say “ok, that’s that.”

19. Do you have very mixed up feelings and ideas?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

20. When you do something that gives you a good feeling:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

it’s certain that you’ll it’s certain that something

go on feeling good will happen to spoil the

feeling

21. Does it happen that you have feelings inside you would rather not feel?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

22. Do you anticipate that your personal life in the future will be:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

totally without meaning full of meaning

23. Do you think that there will always be people whom you’ll be able to count on in the future?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

you’re certain you doubt there will be

24. Does it happen that you have the feeling that you don’t know exactly what’s about to happen?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

25. Many people – even those with a strong character – sometimes feel like sad sacks (losers) in certain situations. How often have you felt this way in the past?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

never very often

26. When something happened, have you generally found that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

you over/underestimated you judged it’s

importance importance well

27. When you think of difficulties you are likely to face in important aspects of your life, do you have the feeling that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

you will always succeed you won’t succeed

28. How often do you have the feeling that there’s little meaning in the things you do in your daily life?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

29. How often do you have feelings that you’re not sure you can keep under control?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

very often very seldom or never

Scoring the Inventory

Before adding up your results, go through and convert the reverse-scored items. For reverse-scored items, choose the opposing values: (1=7, 2=6, 3=5, 4=4, 5=3, 6=2, 7=1). The reverse-scored items are 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 20, 23, 25, 27.

Once you have reverse-scored the above items, you may add up the values of your answers to get a cumulative total.

Figure 1.2: SOC Scoring Key

Comments

Post a Comment