Structure in College Course Design and Facilitation

This post is based on a presentation that I gave at a philosophy of education conference (I gave it along with a student, Michal West, who unfortunately was unable to present.) This is why it has been written in a formal way and with formal citations and so forth.

In what follows I describe what was to me a new insight that there really wasn't that big of a difference between teaching styles that emphasize student-chosen course requirements (student-centered) and those that emphasize instructor-chosen course requirements (instructor-centered). I had hoped to point out how student-centered courses were preferable, but realized that both methods could be helpful for promoting student learning and growth. I also realized that both styles could easily drift too far in their respective directions and become either controlling or chaotic.

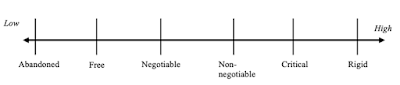

In Figure 1, below, I hoped to put the humanistic teacher Carl Rogers on one of the leftmost notches in a magical zone of student freedom. Then I wanted to put the behaviorist teacher Fred Skinner on the far right. But when I examined their practices, they occupied the middle notches--to the left and right, respectively.

Below is a more detailed breakdown.

FIGURE 1: The Structure Continuum

Degrees of Structure (from High to Low)

Rigid

Rigid classrooms have clear and inflexible boundaries. All learning objectives, course materials, activities, deadlines, and assessments are determined in advance. These are applied to all students without discrimination. Questions from students, unless anticipated in advance and put into a Frequently Asked Questions handout, are forbidden. Dialogue or discussion are also forbidden. Teacher adheres to the Rigid course structure by means of punishment, which is often called discipline. It is the classroom run as prison ward.Critical

Critical classrooms have boundaries, but are less transparent about them than rigid classrooms. This gives the illusion of flexibility. Critical teachers indicate class boundaries by embarrassing, humiliating, and criticizing students. In a rigid classroom, a student who forgets homework loses 20 points or fails (disciplinary control). The same student may be given a chance to make it up in a critical classroom, but they would also be called “lazy,” “irresponsible,” “good-for-nothing,” and so on (i.e., ideological control; See Whitehead, 2017). Critical classrooms communicate that a student’s self-esteem is to be tied to their achievement. Good people get A’s; bad people get F’s and are branded as failures (it is telling that the lettered grade scale conveniently skips over “E,” for which an equally hurtful slogan is hard to find).Rule-bound (Non-negotiable)

Like Rigid classrooms, Nonnegotiable Rule-bound classrooms have clear boundaries. Rule-bound classrooms are different in that rules can be changed, but only by teacher. If students are struggling with Chapter 4, then teacher may choose to spend an extra few class-periods before moving onto Chapter 5.Rule-bound (Negotiable)

Negotiable Rule-bound classrooms are as their Non-negotiable counterpart, except that students have a say in redesign decisions.Free

Students are given full freedom to do as they wish, including the option of doing nothing. They are given full access to materials (including teacher) and freedom to design activities, assessments, or objectives as they see fit.Abandoned

Students are given the freedom to do as they wish, including the option of doing nothing. They may be given access to materials, but they are on their own in doing so. There is no accountability for students or teacher at the end of the term, and no contact with teacher.Summary

Diagramming the Structure of Six Common Instructional Styles

Teaching Machines: Fred Skinner and Behaviorism

Fred Skinner was an experimental psychologist, most notably responsible for the theory of operant conditioning as he applied it in experiments with animals. His achievement was the practice of psychology as an experimental science, every bit as rigorous, systematic, and unbiased as geology or modern physics. His model for conditioning human behavior is still used everywhere from psychiatric hospitals to schools.

Structure with Skinner’s Teaching Machines

Without getting into the technical details of the apparatus, we can diagram teaching machines on the structure continuum. We can do so by examining the care with which Skinner describes teaching machines. He says, for example,

An appropriate teaching machine will have several important features. The student must compose his response rather than select it from a set of alternatives, as in a multiple-choice self-rater. One reason for this is that we want him to recall rather than recognize—to make a response as well as see that it is right. […] Another reason is that effective multiple-choice material must contain plausible wrong responses, which are out of place in the delicate process of “shaping” behavior because they strengthen unwanted forms. (1958, p. 970)

It is clear that Skinner has not merely programmed the teaching machine and set it loose. He hovers over it, making adjustments here and there, and examines the product.

Skinner has a clear and steadfast idea of what learning is, but his instructional practice is more flexible. He is careful not to consult the student in the process, but he very much takes their perspective and perception into consideration; his methods are non-negotiable.

FIGURE 2: B.F. Skinner’s Teaching Machines on the Structure Continuum

Learner-Centered: Carl Rogers

The next learning theory comes from American counseling psychologist and lifelong educator, Carl Rogers: persons-centered or nondirectional teaching. Based on his observations in individual and group therapy, it was Rogers’s opinion that no person can teach another person anything worth knowing. While such direct instruction might appear to work during the short term, long-term observations show that learning of this sort fails to have any lasting significance. If it does have lasting significance, then it is usually at the expense of the student, such that the student would have been better off without it. Because Rogers’s learning theory is so well-known and widely discussed, a discussion of its details will be skipped. For further reading, see Rogers and Coulson (1986).

Structure in Rogers’s Learner-Centered Classroom

FIGURE 3: Carl Rogers’s Learner-centered Approach on the Structure Continuum

Insight-based Learning: Gestalt Theory in Education

Though peculiar in name, the learning theory promoted by Gestalt psychologists can be seen as the first in the long and prosperous line of cognitive and transformative learning theories.

Structure in Insight-based Classrooms

We will use the insight-based problem-solving protocols outlined in Köhler’s observations with chimpanzees. The objective was for the chimpanzees to get the bananas, which were many feet higher than the chimpanzees could reach. To solve their problem, the chimpanzees would have to devise a strategy for reaching them. Around the room were objects such as fruit crates and poles. No tool by itself was sufficient for solving the problem. The tools had to be used together. Chimpanzees were given no instruction.

FIGURE 4: Insight-Based Learning on the Structure Continuum

Radical Pedagogy: Paulo Freire’s Cultural Circles

With a growing emphasis on social justice, equality, equity, and so on in education, Paulo Freire’s radical pedagogy (2013, 2018) has remained relevant.

Literacy lessons began after the cultural circles. Students were not hampered by the schedule, but regularly skipped far ahead by reading and writing phrases and sentences convention says they shouldn’t be able to.

Structure in Freire’s Radical Classroom

The students were responsible for the learning objectives, not teacher. This represents a measure of freedom. It was the combination of student goals (become literate) and instructor techniques (cultural circle, lessons) that created Freire’s radical classroom.

FIGURE 5: Freire’s Radical Pedagogy on the Structure Continuum

Lecture and then Test: Conventional Instruction

In the Lecture – Test model, teacher gives long speeches which cover information—usually limited to the contents of a textbook chapter. The speeches are judged by the volume of information communicated and their level of entertainment. Students are periodically tested, quizzed, and exam-ed over the lecture materials, and are encouraged to make changes based on the feedback they receive (i.e., their grade on the test, quiz, or exam).

Structure in the Lecture-Test Classroom

FIGURE 6: Lecture – Test Classrooms on the Structure Continuum

Comparing Structure across Models of Learning

With the exception of the Lecture – Test model, the theories of learning do more converging than diverging in terms of structure. This convergence can be seen in Figure 7. What they have in common is the instructor’s willingness to make changes to the rules (expectations, outcomes, assessments, and so on) based on feedback from the classroom. When looking only at structure, the fundamental differences between learning theories are what qualifies as data for feedback, which can either come from teacher insight (as with Skinner’s teaching machines), or combined insights from teacher and student (as with Rogers’s Learner-centered approach). Instructor insights for course structure are present in each of the models, including the Learner-centered approach. Though Rogers has given considerable freedom from the student, he has still gone through the trouble to organize course materials, listing requirements, and participating in the learning process as it unfolds in the classroom.

FIGURE 7: Five Learning Theories on the Structure Continuum

Summary of Structure Continuum in Education

After diagramming six theories of learning, models which span the breadth of the author’s imagination for classroom structure, it is apparent that learning theories share much in common when it comes to structuring the learning experience. The most significant conclusion is that the instructor’s job is not finished once the course begins—they must continuously watch, evaluate, and assess how the course is going, and make changes for the purposes of improvement. Where learning theories don’t overlap, their difference is only with respect to whether students are capable of generating insights or contributing to course objectives, materials, and so on.

References

Freire, P. (2013). Education for critical consciousness. New York: Bloomsbury.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed, 50th Anniversary Ed. New York: Bloomsbury.

Gazzaniga, M. S., & LeDoux, J. E. (1978). The integrated mind. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Gatto, J.T. (2017). Dumbing us down: The hidden curriculum of compulsory schooling, 25th

Goodman, P. (1964). Compulsory mis-education and The community of scholars. New York:

Vintage.

Kohn, A. (2018). Punished by rewards: 25th anniversary edition: The trouble with gold stars,

Postman, N., & Weingarter, C. (1971). Teaching as a subversive activity. New York: Delta.

Rogers, C. (1961). Personal thoughts on teaching and learning. In C. Rogers, On becoming a

Rogers, C. (1986). My way of facilitating a class. In C. Rogers & C. Coulson, Freedom to learn,

Rogers, C., and Coulson, W.R. (1986). Freedom to learn. Princeton, NC: Merrill.

Skinner, B.F. (1958). Teaching machines. Science, 128(3330), 969-977.

Tenenbaum, S. (1961). Student-centered teaching as experienced by a student. In C. Rogers, On

Whitehead, P.M. (2018). Dangers of fact-minded education. In P.M. Whitehead, Education in a

Press, 103-114.

Comments

Post a Comment